Note to subscribers: sorry for not posting last week. This week’s post is in two parts. The first part continues the loose “series” on my memories of altered states 25 years ago, which started on Feb 7 with Toward the integration of spontaneous psychedelic experience.

The second is about how I’m giving up scrolling for Lent – so if you’re also grappling with phone addiction and are curious, then (ironically) scroll down…

The Whole Point: remembering when distance disappeared

It’s difficult to know how to remember that time.

Perhaps it began one grey day in late 1999, in the overgrown back garden of the big, ramshackle shared house on Telegraph Hill. It was starting to rain - widely spaced, heavy drops - but I stayed out there, my gaze fixed on the vivid pink and green of a flowering bush, drops of water slowly suspending themselves from the edges of petals.

I knew - from reading or lectures?1 Or just from thinking about it? - that what I was seeing was an image in my own mind, an illusion created by my eyes and brain. I had thought about this before, but on this particular day it struck me as profoundly tragic. There was no way to see what was actually there: no way (it seemed) to connect with this bush, or the other living beings around me. I was alone in a world of my own projections.

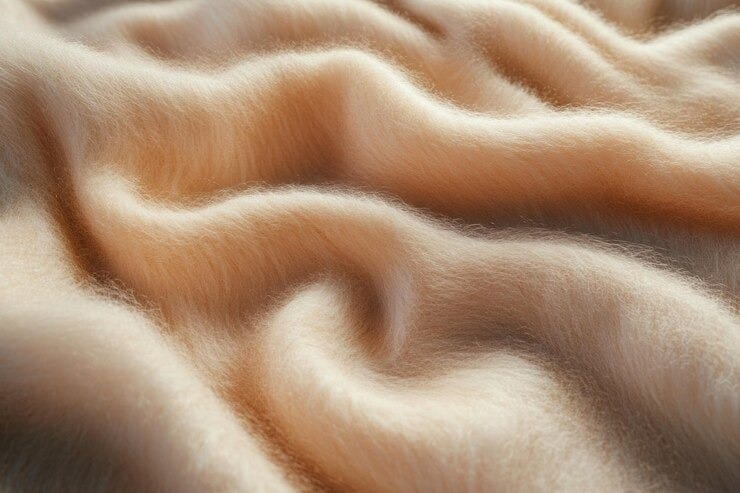

Later, I lay on my stomach on the bed in my basement room, staring at the tiny fibres that stood out from the surface of the blanket below me. I could get as close as I wanted, see them in minute detail, but there was still no way to know what was really there - only what my own particular sense-apparatus and knowledge-system was capable of seeing.

Although this thought may have started on an intellectual level, I felt it emotionally as an unbridgeable loneliness, and soon it began to register viscerally – that exact word came to mind at the time – as an impression that permeated my entire somatic felt-sense, spreading outwards from my guts: the impression of being suspended in a void, an abyss.

Yes, there was still gravity, and the ground beneath me, and seemingly solid things all around that I could see and touch. But some part of me that wasn’t the senses seemed to be in charge now, and had its own awareness, independent of these sensory impressions. What that awareness knew - with a kind of knowing that seemed to be embedded deep in my belly - was that there was NOTHING THERE.

Was I experiencing depression? There was something of that - for some weeks, at least a couple of months, my mood had gone beyond mere sad emotion into something that felt like a physical heaviness; every step felt difficult, slowed down. But this sense that the apparently solid world around me had fallen away - revealing emptiness - was new, and had an objectivity, a quality of undeniableness, that was more than a passing state of mind. It was surprising, like seeing something new, and wishing I could un-see it, but I couldn’t.

How much of what I’m describing is based on direct experience, and how much is interpretation, influenced by what I subsequently read? A book that showed up during this period was Ouspensky’s “Tertium Organum” (1922), a paperback I found at a second-hand book fair in Goldsmith’s College hall, with a front cover graphic reminiscent of the inside of a computer. Within its pages I found an idiosyncratic metaphysical perspective that was both reassuring - its musings had enough in common with my own experiences to suggest I was onto something real, and not the first to have navigated such states - and at the same time disquieting, because it was so far from what I felt comfortable discussing with others, and its grandiose tone led me to suspect that only eccentric and self-absorbed people might be my companions in this new dimension, or that I might be such a person myself.

Nevertheless, its presence was in some way a case of “the teacher appearing when the student was ready”, entering my life at the very moment I became able to understand (at least in part) what it was talking about.

I discarded the book a few years ago, in one of my periodic efforts to prune our household’s ever-growing volume of books, but the chapter that I remember most is available online here.

It was startling, the first few times I thumbed through the paperback, to find passages such as this reflecting my own experience with alarming precision:

“Truly what is infinity, as the ordinary mind represents it to itself?

It is the only reality and at the same time it is the abyss, the bottomless pit into which the mind falls, after having risen to heights to which it is not native.

Let us imagine for a moment that a man begins to feel infinity in everything: every thought, every idea leads him to the realization of infinity.

This will inevitably happen to a man approaching an understanding of a higher order of reality.

But what will he feel under such circumstances?

He will sense a precipice, an abyss everywhere, no matter where he looks; and experience indeed an incredible horror, fear and sadness, until this fear and sadness shall transform themselves into the joy of the sensing of a new reality.”

I have already written, in brief, about my first experience of that “joy of the sensing of a new reality”. By the time I found the book, I think, that breakthrough had already occurred.

Today I want to remember one of the “strange new experiences” mentioned in that post – experiences that followed in the weeks and months after that first moment of seemingly inexplicable knowing that “everything will be all right”.

This one was an awareness that grew in me slowly, as if I were looking around after waking up in a new place, gradually noticing the features of my environment.

I began to notice that - where previously I had sensed an abyss, an infinite emptiness - instead there was an impression of no distance at all. No distance between me and any other being, place or time. In the same way that physical objects had previously started to feel like illusions, now time and space felt like illusions.

One winter afternoon, as I sat in my counsellor’s office at the back of the doctor’s surgery on the university campus, looking out at a tree that was dimly visible against the twilight sky in the glow of a streetlight, I found that tears were pouring down my face: tears of unbounded joy, for no reason but that I felt so close to the tree, the tree was so beautiful, and it was inseparable from me.

The counsellor gazed at me, confused but smiling. I had come to her, a few weeks earlier, to discuss my depression and the sense of fragmentation and meaninglessness I was experiencing. Now, suddenly, there was the opposite: everything had a mysterious inner glow.

I had an occasional job at the time that involved counting traffic. I’d been given a clicker with different buttons for cars, vans, articulated lorries, and so forth. One day I remember being sent somewhere where I sat on a park bench, slightly up a hill, and watched the traffic on the road below, clicking for each vehicle. What stands out about this memory is that I started to feel there was simply no distance between me and the hedge at the bottom of the hill, the passing cars, or the clouds above, whose movements I seemed to know before they happened. The whole scene was already within me, and a strange ecstasy came with this knowing.

My mind’s attempt to visualise the reality that I now perceived2 looked like simply a dot, a point, with no dimensions at all, in which everything coexisted. It reminded me of the concept of the Big Bang, the idea that all matter had once existed packed together in impossibly dense form, before exploding into what would become the universe as we know it. But now, the notion of a “before” seemed illusory - specific to normal waking consciousness, not intrinsic to reality itself - while the point in which it, or we, all existed together was clearly still here in the (eternal) present.

In Ouspensky’s book this state is referred to as ‘consciousness, wide as the sea, with "its centre everywhere and its circumference nowhere”’.3

Eleanor Robins’ post on “imaginal ancestors”, published last summer, reminded me about Julian of Norwich, whose words had come to mind with my first spontaneous psychedelic experience: “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well”. After reading Eleanor’s post I was moved to purchase a copy of Julian’s book “Revelations of Divine Love” (first published in the 14th century), and was surprised to find that one of her visions was of “God in a point”:

“I saw God in a Point, that is to say, in mine understanding,—by which sight I saw that He is in all things.”4

A further reminder came with Left Brain Mystic’s recent post (which I won’t attempt to summarise here but is well worth a read) that ingeniously re-interprets the question "How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?” as follows:

“After all, how many different ways can reality observe itself from a single location? How many unique perspectives, each reflecting the universe from its own angle, can coexist in a dimensionless point of consciousness? Suddenly that medieval question starts to sound less like idle speculation and more like a profound inquiry into the nature of experiential space.”

Aren’t we each one of those unique perspectives, each reflecting the universe from our own angle, yet - in a reality beyond senses and concepts - all existing in a single location?

Giving up Scrolling for Lent

I don’t know if I need to explain to anyone here why the habit of scrolling infinite feeds in a phone app feels unhealthy. It’s a kind of bingeing for the brain: my consciousness ends up stuffed full of so many different concepts, questions, and unfinished loose ends that it can’t possibly digest everything, and is constantly exhausted by the struggle to do so.

I deleted Facebook a few months ago (I’m a little too old to have the same problem with Instagram) but my habit immediately transferred itself to Substack Notes. The content feels healthier, but the indigestion after overdoing it remains the same.

I contemplated giving up my smartphone completely, but I rely a lot on maps and Citymapper for finding my way around by public transport in London, and the Careem taxi app when I’m in Iraq, and WhatsApp has become the primary way most friends communicate with me. Anyway, I realised that for me, the biggest problem isn’t the phone itself but the specific behaviour of scrolling. It has – for me as for so many of us – got worse and worse over the years as those clever algorithms learn all about the hot topics and emotional triggers that make us pay attention. And yes - it’s the billionaires we are literally paying with that attention, which we divert from our immediate circles to whom it might make more of a difference. I look back with nostalgia to the early days of social media when what you’d see in your feed was only the people you’d chosen to follow, and their posts appeared in exactly the order that they posted them. It told you something about your world and the people you knew - rather than just telling you more and more about yourself and extrapolating on your own obsessions.

When I talk about giving something up for Lent, I want to clarify that I don’t consider myself a Christian, although I was brought up with that heritage (going to church until I was 16). However, Lent has brought itself to my attention this year, mainly because I noticed how closely this year’s dates overlap (at least at the start) with Ramadan, the equivalent Muslim season of fasting (Ramadan began last Saturday 1st March, Lent followed on Wednesday 5th). Since my work is based in Iraq – I’m currently back in London but still working closely with people there – Ramadan is a big thing, and I’m interested in how such a society-wide observation of the fasting practice changes people’s consciousness. There was a recent article here on Substack which I can’t currently track down, but it talked about how the point of Ramadan is to practice being uncomfortable, to increase your threshold of tolerance towards what is effortful, so that year-round, the discomforts and challenges of life are not enough to divert you from living your principles.

I feel this is a practice I could also benefit from, so I looked to my Christian heritage and decided to mark Lent. The obvious thing to give up was my scrolling habit. To be honest, I’m hoping to keep it up after Lent too, but committing to a fixed time period in the first instance (up to Easter on 20th April) feels more manageable.

If you’d like to give it a try too, here are the steps I took:

Deleted from my phone every app that includes an infinite scroll among its features. For me this included the Guardian, Al Jazeera, and other news apps as well as Substack (my current main scrolling time-suck, in the form of Notes - which of course pops up first when you open the app) and Instagram (which I don’t use much, but fear I might gravitate towards after deleting the others).

Decided on a specific way to occupy my brain when the urge strikes to reach for my phone. Actually I have two ways now. The first one I thought of was to start thinking about my friends, and reflecting on where I might have an unfinished conversation or a reason to reach out. After all, that’s supposed to be the point of social media, right? Being social! So I haven’t totally banned myself from using social media, I can still do it on my desktop (and I still have WhatsApp and other messaging apps on my phone), but only when I have a specific person I want to contact and something to say to them. The idea is to switch into being an active agent of communication rather than a passive consumer.

The second way of occupying my brain (which is simpler, but more specific to me) is having an Arabic word of the day to learn. At first I downloaded an app for it - which just goes to show how brainwashed I am - but then I realised I already have a box of flashcards and an Arabic-speaking husband, so there’s no need to pay for an app! My word for today is استمر (“istimer”), meaning “continue”. You could do the same with any language you want to learn. A close alternative is to choose a short quote - a line of poetry perhaps, or a short prayer or mantra of some kind - that you want to remember and reflect on. Choose it at the beginning of the day; then, each time the urge arises to grab the phone, just recite your word of the day (with variations if you like, such as conjugating a verb and putting it into sentences) or your chosen quote. Take the time to appreciate the value and multifaceted meaning of that one small piece of knowledge, instead of reaching out for more, and more, and more.

Ramadan kareem and blessed Lent everyone!

It may have had something to do with Kant’s “ding an sich”, or Gregory Bateson’s comment in Steps to an Ecology of Mind: “How many of you agree that ‘you see me?’ - then I guess madness loves company.”

I’m not sure perception is the right word here, implying as it does the involvement of the senses. I would say this was more like intuition or just knowing.

The full passage can be found here: https://www.wendag.com/tertiumo/tert19.htm

Quote taken from the version of Julian’s account of her revelations here.

For further explication of the meaning of the “point” and other literary references to it, I recommend this footnote.